Copenhagen, Denmark (2004)

![]()

In early 2004, I'm minding my own business in my office, when I get a call. It seems that an architecture professor at the University of Florida has heard that I know a fair amount about bicycling, and he is leading a studio of students to prepare a bicycle master plan. Part of his studio is to take groups of students to see model communities for bicycling. He asks if I'd be interested in joining a group going to Copenhagen-he'd pay my air fare out of the grant money he has.

I can assure you that he did NOT have to twist my arm. Indeed, I nearly leapt out of my chair, as I was so delighted over such good fortune.

I had heard a number of stories over the years about the cosmopolitan wonders of Copenhagen, and suddenly, shockingly, I'd actually be there to see it with my own eyes...in less than a week.

In the three or four days before the trip, I was so convinced that the trip was too good to be true that surely something would come up that would terminate this dream opportunity. My employer would deny my trip or my vacation request. The professor would change his mind about taking me along after hearing more about my high-octane bicycling views. The US would cancel flights to Europe over terrorism fears. I'd come down with a terrible cold. The airline would go out of business.

But the day arrives. I find myself sitting in the Toyota Forerunner of the professor and his students as we drive to the Orlando airport.

Along the way, we chat about effective and ineffective transportation strategies, and go into the details of our planning philosophies.

At the airport, we are amused to find that despite what our tickets tell us, our flight is NOT on Continental Airlines. Instead, we are to board VIRGIN Airlines. More so than my trip companions, I am especially amused because I've recently learned from an old high school friend (a guy that owns a company which names businesses and products) that he is wildly impressed that an airline has decided to call themselves "Virgin."

After all, he says, what sort of images are conjured up by the word "virgin"? For most people, a virgin is someone who doesn't know what they are doing. They are inexperienced. As my friend points out, are THOSE images the ones that an airline would want to convey??

His answer is fascinating.

Yes, those images are not what an airline would want potential customers to associate with the airline, but he also notes that people subconsciously assume that for an airline to exist and be operating, it MUST have FAA certification and must therefore be competent. Indeed, the name most likely is quite effective in attracting customers because the airline has effectively set itself apart from its competition-competition that has chosen obvious names such as "Continental" or "American" or "United."

As it turns out, the key question for his naming company is how to convince a company that such an edgy, risky name is actually an ally instead of a liability. Too often, he points out, a company will ask a large number of its employees to come up with a consensus as to a preferred name. The inevitable result is a name that is obvious, safe, lowest-common-denominator, and deadly boring. A sure recipe for NOT setting a company apart from its competition.

On the contrary, Virgin Airlines seems to proudly revel in their name.

Not only is our Boeing 747-700 being flown by a company called "Virgin," but the side of the jet carries, in bold, large black letters, a nickname: "Hotlips." Just as I notice this, the largest parade of airline stewardesses I've ever seen (about 30 of them) board a plane are heading to board "Hotlips."

And they are all wearing hot, unvirgin-like red dresses...

Hardly a virgin, this plane.

The plane itself is COLOSSAL in size. A double-decker 747-the "Queen Mary" of the fleet. A glimpse from inside the terminal gave the impression that this KING KONG jet would dwarf even an aircraft carrier.

We board our plane after the now obligatory, seemingly endless security checks and luggage inspections. Soon after we are underway, the on-board computer informs us that our flight from Orlando to London over The Big Pond will be 7 hours and 20 minutes.

We take off 4,350 miles from our destination in London.

Arrival in Copenhagen immediately sends the message that we have arrived in a cosmopolitan, contemporary city. The shops in the airport, for example, are exceptionally upscale for an airport.

Oddly, we also quickly notice a rather sophomoric aspect of the city. Both a retailer and a number of shirts worn by young people contain the term "FCUK".

Also, I am quickly disappointed to find that the Danish are like many other Europeans in an unfortunate way. Nearly everyone-young and old-is a chain smoker. I've never come up with a theory about why this is so prevalent in Europe.

The city metro system offers the city the civilized amenity of serving the municipal airport-unlike nearly all large American airports, where the lack of transit service or use means that the airport is choked in automobile congestion.

As we leave the central downtown train station, we immediately realize we are in a more impressive world. Just outside the doors are parked what seems like THOUSANDS of bicycles. Clearly, a number of Copenhagen residents commute by bicycle to the station, then use the train to get to their destination.

We set out, on foot, for our hotel a few blocks away. We quickly learn that most downtown streets are rather medieval in design and human-scaled in size (that is, modest rather than Interstate-sized).

Many of the streets are set off by granite bricks instead of asphalt, or colored blocks.

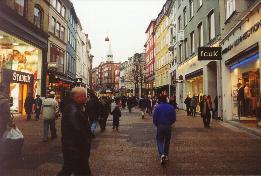

Downtown Copenhagen is graced with a delightful (albeit small) network of "walking streets." While we were there, and despite the overcast, frigid (28-34 degrees Fahrenheit) weather, we find these streets to be vibrant, throbbing, fun-loving, heavily-used places for the city residents to socialize, be friendly, smile, laugh, be animated and experience the walking joys of serendipity. All of which are largely denied to Americans, who have traded off these humanizing pleasures, and a quality transit system and public realm, by instead opting for auto dependency, hyper-consumption, creation of a luxurious private realm, social isolation, fear and distrust of others that such a lifestyle inevitably brings.

An unusual feature on some of Copenhagen's larger streets is a somewhat separated bicycle lane. The design features travel lanes for cars, then sometimes a semi-separated bus lane, a stone curb, then a slightly elevated bicycle lane, then a sidewalk area. Each of these travel ways tend to butt up to each other rather than be separated by landscaping. In a few cases, the bicycle lane is separated from the car lanes by a layer of on-street parallel-parked cars.

Both arrangements provide downtown bicycle riding that feels relatively safe for bicycling.

On most city streets, however, the Copenhagen system has bicyclists share the travel lane with cars, an arrangement I generally advocate when, like in Copenhagen and many American downtowns, car speeds are modest. Bicyclists sharing lanes tend to be safer since they are more visible and more predictable to motorists.

And again, despite the icy weather, we see LARGE numbers of people riding bicycles on these routes-clearly commuters. Astoundingly, the bicyclists seemed to come from the entire cross-section of residents: seniors, middle-aged professionals, young adults, teens, and most impressive of all, a number of women I would classify as "glamorous" in the sense that they wear high heels, make-up, dresses, stockings, and fashionable coats. Many are parents who tote their young children in a child-carrying trailer usually mounted in front of the bicycle in the same way that many Asians tote food for sale in the Far East.

The large number of bicyclists have a pleasant effect on me as I bicycle about the city. Unlike in my Gainesville home, I bicycle without any sense of humiliation, even despite the fact that I am riding a cheap, 3-speed WOMEN'S bicycle. In Gainesville, usually as the lone bicyclist on the road, I often feel silly as I, a 44-year old professional, pedal around town. Hard to imagine how embarrassed I would feel in Gainesville if I were on a women's bicycle. Obviously, the fact that a large cross-section of Danes bicycle all the time makes me feel almost HIP as I cruise around on my silly 3-speed. It almost seems as if it is the MOTORIST who is the oddball geek in Denmark.

As an aside, I would attribute the large number of bicyclists not so much to the admittedly outstanding bicycle routes laid out, but from the fact that car travel and car parking is clearly burdensome and costly, which leads large numbers to rationally conclude that bicycling is financially prudent and more convenient than trying to travel by Ford Explorer.

At this point, I should also mention that like other European nations I've visited, it is curious to notice that despite the overall high-quality provisions for bicyclists, the bicycle parking racks are nearly all unacceptable from my point of view. Almost none of them provide frame support, protection from vandalism, or scratch protection. It is evident that the Americans may not have more than a tiny number of bicyclists in comparison to Europe, but we tend to greatly exceed the Europeans in the provision of bicycle parking facilities. It is one of the very few things that I take pride in about how we do transportation in America.

We at least respect, in many cases, the PARKED bicycle (perhaps out of a sense of guilt).

Other impressive features we see are modest, post-mounted traffic signals for bicycles, which informs the bicyclist when to stop or proceed. At most intersections, bicycle lanes passing through the intersection are clearly marked in blue paint and separated from the pedestrian crosswalks (which are often honored and made safe by being carried on elevated "speed tables").

At crosswalks, the signals are timed to provide a crossing signal relatively quickly, which means that pedestrians and bicyclists are not overly burdened by the delay of waiting for the light to change. A very important benefit, which is only exceeded by intersections not controlled by traffic signals at all-such as at intersections controlled by a roundabout or traffic circle.

Because of these respectful, considerate features for bicycles and pedestrians, we notice that in Copenhagen, pedestrians and bicyclists tend to respect traffic signals and crosswalk signs. Unlike much of America, we see only a small number who don't obey the signals. Instead, they tend to respect the regulations, perhaps because they feel respected AS PEDESTRIANS AND BICYCLISTS. We also notice that motorists tend to respect and be courteous to bicyclists and pedestrians, generally making them feel safe and comfortable. The motorist in Copenhagen typically and politely pauses, patiently waits and otherwise provides a lot of breathing room to a nearby pedestrian or bicyclist seeking to cross or is within proximity of the vehicle travel lane. By stark contrast, most American motorists tend to find great pleasure in intimidating, harassing and otherwise recklessly ignoring bicyclists and pedestrians.

We find that one of the many pleasant features of Copenhagen is that nearly all of its citizens tend to be quite trim, fit, healthy and very attractive-no doubt due in part to the fact that many of them seem to engage in a good deal of bicycling and walking as part of their everyday lives. At this northern latitude, the Nordic, Scandinavian influence was rather obvious, as a noticeable number of women sport striking blonde hair and blue eyes.

Curiously, a great many Danes wear black coats, sweaters, shirts and pants. Perhaps to set off the light-colored hair??

The cost of living in Copenhagen is clearly quite high. I notice this especially on a night out on the town, in which we go to an authentic Copenhagen pub to sample Carlsberg, one of their indigenous beers (the other is Tuborg). A glass left me $7.50 poorer.

Interestingly, the culture seems to be relatively modest, as I notice a large advertisement along the side of a building facing a public plaza. The ad proclaims "Carlsberg: Probably the best beer available." NOT that it IS the best beer in the land. PROBABLY is timidly suggested by the company.

As I had perceived beforehand, my days in Copenhagen seem to confirm that the nation is not really known for its cuisine, its wine, or even its beer. But even if it is just known for its outstanding cities, that would be sufficient for me to conclude that the culture is to be admired throughout the world.

Of course, the Danes are known for their DANISH, which obligated me to sample some of the authentic local faire. Quite good.

Because Copenhagen is so delightfully cosmopolitan, the lack of an outstanding native cuisine does not mean that one must go without culinary delights while in Denmark. On two separate occasions, we thoroughly enjoyed stupendous meals at authentic Italian restaurants-one of which, I am impressed to report, serves FRESH, HOMEMADE pasta dishes (La Vecchia Signora -- the other was Via Veneto in Malmo Sweden). We also had an excellent lunch at an authentic Thai restaurant. In all cases, our meals were so large that we were generally unable to eat everything on our plates, which is quite astounding, given my own reputation for eating everything in sight due to my voracious appetite.

Sadly, I find that the charms of Copenhagen are being harmed. Outside of its core area, there are large roads (including overpasses) that create an auto-oriented, sterile, suburban character. Unlike the core-where uses are traditionally and compactly mixed-we find that in the suburbs of Copenhagen, the residential-only pattern we see so much of in suburban America is evident. Even in Copenhagen, when the roads grow in size, the car becomes king. The hopeful sign, however, is that even in suburban Copenhagen, residential densities seem relatively high, with 3-5 story rowhouses and townhouses.

Our lodging while in Copenhagen is within the Hotel Maritime. I would recommend the place. Modest in price, yet close enough to be a relatively convenient walk to the "walking streets" of downtown Copenhagen. Indeed, each time we walk or bicycle back to the hotel, we find ourselves able to walk a Walking Street. The complimentary breakfast served at the hotel each morning provides a very good selection-buffet-style-and provides more than enough food for even the biggest appetites.

On our final day, we visit the city of Malmo, Sweden. It is a city of 266,000 people, and we visit because in the week before this trip, I am told by 3 different people that if we visit Copenhagen, we should also visit Malmo. I am intrigued, and we end up adding it to our itinerary.

So on a Sunday morning, we board the Copenhagen train for a very soft, pleasant, convenient trip across the sea into Malmo-a train that, unsurprisingly, is designed for carrying bicycle commuters. Our crossing over the sea was interesting, as it was over a bridge of many miles in length. We pay $30 for the round-trip.

We disembark at the Malmo station and again are ASTOUNDED by what seems like THOUSANDS of bicycles parked just outside the station on a concrete barge on a canal.

Like Copenhagen, Malmo is delightful. Filled with multi-story masonry buildings that are richly, beautifully ornate and historic, they are pulled up to abut sidewalks (photo at right). What this creates is an ambience in which nearly every street is human-scaled and turns out to be sheer joy to bicycle or walk. I very quickly shoot through the rolls of film I bring along, unable to resist shooting almost every street we come upon. Malmo contains a great many outstanding bus stations that are impressively designed to provide an "intermodal" link between the bicycle and the bus or train.

Sadly, and again like Copenhagen, Malmo has a ring of sterile, car-oriented suburbs and larger roads feeding suburban shopping centers.

More so than in Copenhagen, Malmo contains a good number of TWO-WAY bicycle paths and routes, including a particularly outstanding example near its downtown, where what appears to be a multi-lane "bicycle highway" has an underpass under a city street, and steps and bicycle loops that connect bicyclists and pedestrians to the street overhead.

I experience a number of "small world" coincidences during this trip. For example, while on my flight to Copenhagen to evaluate their bicycle program, I find myself reading a book by Roberta Brandes Gratz called "Cities: Back From the Edge". It turns out to be an enormous coincidence. While we are rocketing toward Copenhagen, I learn that Gratz is an advocate of the quality transit I am about to experience in Copenhagen, for she notes that "transit alternatives should be a self-interest priority for car drivers." That while she accepts the fact that a number of people in American cannot imagine themselves getting around without a car, she also asks if such motorists would like OTHER drivers to "switch from cars to transit and leave more road room for them."

The author is dismayed to report that "some European countries seem in a race to catch up with us in our economy's overdependence on the automobile and highway building industries," she also assures the reader that "none have either sold off their train networks to private interests or dismembered their delicate mass transit systems to the degree we have since World War II." Just as our plane sets down in Denmark, I read that "Denmark...[has] many programs reflecting a whole spectrum of success that seeks to support compact growth plans...and keep transit reliable, frequent and reasonably priced. Many...cities have special auto-reduction standards per year. Everywhere in Europe, gas prices are higher than in the United States. In fact, gasoline is probably the ONLY consumer good that is cheaper in real dollars in the United States than it was before the 1973 gas shortage...It costs less to drive 100 miles than almost ever in our history...Pedestrianized communities often have the strongest local economy."

While we only have time to get a brief taste of Denmark, I am frustrated to learn that we will not have time to see other towns in the region, such as the Dutch town of Houten. Gratz points out that in Houten, "50 percent of all shopping trips are by bicycle, two-thirds of household budgets are spent within the town." I make a mental note to see Houten on a future trip to Europe…

Gratz points out that Copenhagen is "one of the world's most civilized and best loved cities." She looks with approval at Copenhagen's transportation strategies—particularly what they do about parking. Gratz indicates that "2 percent of the city's parking has been removed each year for 30 years." Has this caused gridlock? Economic ruin? Apparently not. "Car traffic still flows smoothly through the city and has increased as more people come. Traffic surely has not increased as much as it would have if limiting measures had not been in place. Stability reigns. The economy thrives. No periods of overheated growth, no massive demolition, and no high-rise overkill has occurred."

"In some Danish communities," according to Gratz, "when parking spaces become scarce, the price for parking is raised. (Toronto does the same thing, using the price of parking as a traffic control measure.)...No parking lots at all are provided at schools. Students bike or walk. (The United States is probably the only country in the world with an expensive, single-use rubber tire transit system devoted exclusively to transporting children to school. It is a monumental burden for local public school budgets.)" The author strongly urges others to see the downtown benefits that the Danes have experienced as a result of their planning. "Every American public official, planner, or traffic engineer at all interested in promoting the stabilization or rebirth of American downtowns should visit Danish communities."

Gratz reports a mind-boggling experience (for an American, at least) as she walks down the middle of a Copenhagen Street, where she is astonished by the scene in front of her. "A small delivery van was slowly following directly behind three women, one of whom was pushing a stroller. All three were in deep conversation. The women were oblivious to the vehicle's presence. The driver did not honk, but just waited for them to reach a corner at which he was turning...Sure enough, I was being followed in a similar fashion by a 'walking' vehicle whose driver was undisturbed and unagitated."

In Copenhagen, "drivers accept limitations," she finds. "Bicyclists proliferate. All kinds of safety statistics improve. More significantly, traffic calming is much cheaper than building more bypasses that bring short-lived congestion relief, and it does not open new land for sprawling development."

Gratz concludes that there is no reason for Americans to decide that the civilized life experienced by Danes is unavailable to Americans. "...The idea that these conditions are not as applicable to where we live as to where we choose to visit is bizarre..." Her recipe is to tame the car, as it "has become an impediment to both mobility and community. The only choice is to undo excessive dependence on it."

I also find personal coincidences in reading this book. The author uses 3-4 pages to quote statements from a woman who was previously a supervisor of mine in the Gainesville Planning Department (she now works in NYC). The author mentions attending a conference in Toronto in 1997 that I ALSO attended. She refers to a study about the costs of sprawl authored by a Florida State University professor I studied under and befriended in the early 1980s, and notes how this study influenced a town to establish an open space acquisition program. The town, in upstate New York, is just down the road from where I grew up. Finally, the author refers to a central Florida city which has seen its downtown decline due to suburbanizing highway strategies. The coincidence is that over the past few years, I have given two speeches in this small city about traffic congestion, suburban sprawl, and a declining quality of life due to excessive car dependence.

One of the most impressive features I notice in Copenhagen, a relatively large city of 1.7 million residents, is that for all of the 3 days we are there, I see not a single police officer. In addition, I hear only one emergency siren for that entire period. Quite stunning, given the fact that I live in Gainesville, Florida, a city with 17 times less people than Copenhagen, yet I see a good many police officers each day in Gainesville. In addition, emergency sirens are nearly continuous throughout the day and night. (The sirens are so noticeably absent that I would be comfortable in speculating that Copenhagen is perhaps the quietest large city in the world). It is clear that the residents of Copenhagen have done well in funneling much of their public tax revenue into the quality of life in their public realm rather than fearfully squandering most of their wealth into law enforcement and emergency services.

In America, we've opted for a cornucopia of consumer goods in our privatized "me generation" culture. The trade-off is that we have lost-particularly in our young people-a sense of civic responsibility, a sense of respect for laws, a sense of community, any semblance of a quality public realm, a cultural memory of how to build a community designed for people instead of cars, and a civilized, affordable and choice-rich way to travel.

Back to Dom's Voyages and Adventures page.