Thursday, October 24 2002

| RETURN OF THE SATYR PLAY

Bat Boy: The Musical

Hippodrome State Theatre

October 18 – November 10, 2002

375-HIPP |

|

|

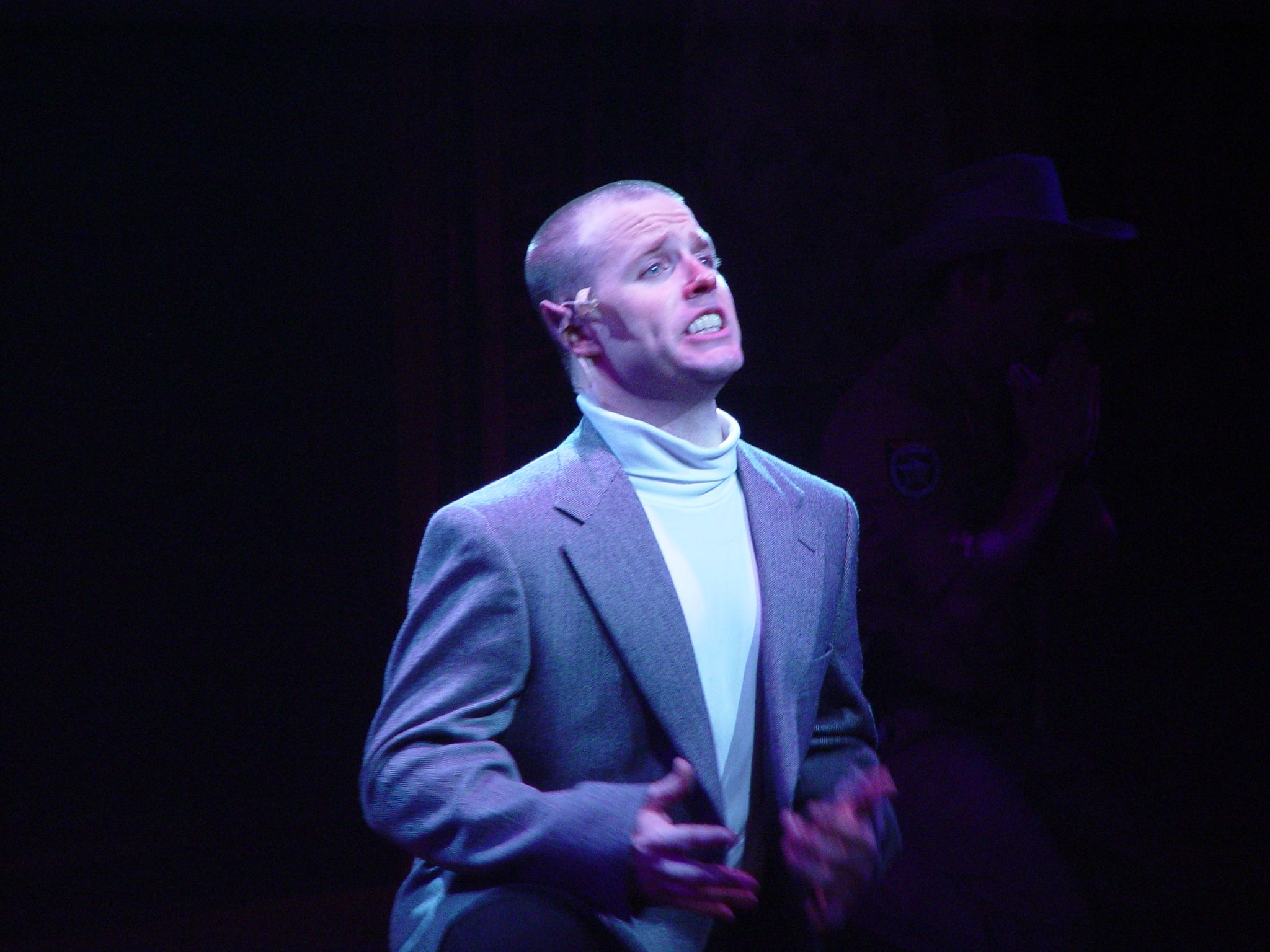

Chad Hudson as Bat Boy

SCENIC DESIGNER - Mihai Chiupe

LIGHTING DESIGNER - Robert P. Robins

PHOTOGRAPH TAKEN BY - Rusty Salling

CLICK HERE TO SEE MORE PHOTOS

|

At the annual playwriting festival in ancient Greece, the winners performed

their tragedies, comedies, and satyr plays.

Aristotle’s treatise on tragedy is well preserved in The Poetics.

What Ari had to say about comedy disappeared, probably in a puff of smoke,

when the library at Alexandria burned (only to be fictionally recovered

in Umberto Ecco’s haunting The Name of the Rose).

But what of the satyr play? Seemingly it went the way of the satyrs

to a great debauch in the underworld.

Now, triumphantly, the satyr play rises from the kingdom of the dead

and takes soaring flight in the figure of Bat Boy: The Musical.

The purpose of the satyr play was to make fun of tragedy. It’s where

we get our notion of satire. The satyr play took the themes of the winning

tragedy at the City Dionysia and twisted them from the sublime to the ridiculous.

Did I leave out lewd and lascivious? Don’t worry; the Hipp doesn’t.

Leaping libidos, naked frolics, and as beautiful a pair of freckled

boobs as you’re ever likely to see, Bat Boy has it all. No wonder he craves

humanity.

Bat Boy: The Musical is the satyr play meant to accompany director

Lauren Caldwell’s masterpiece Frankenstein (1999). That play’s themes

are here waxed and sent skimming like a surfboard riding a tubular wave.

An all-star cast, onstage and off, has forged a plaything that is pliable,

precise, satiric, and joyful.

The playmakers have made an investment of energy, not to mention budgetary

concerns which must have been monumental, to produce an airy nothing. But

it works. Because they work it.

But first let us be mindful of the caution set forth by Brecht in his

great poem "On Everyday Theatre."

Brecht warns, "You artists who perform plays in great houses under electric

suns," a fitting description of the jewelbox that is the Hipp and the lightning

strokes of Robert P. Robins’ illuminations, "do not like parrot or ape/

Imitate just for the sake of imitation, unconcerned/ What you imitate,

just to show that you can imitate."

Even more than the play, which is silly yet serviceable, it is the players’

own energy, their hard work, their devotion both to their craft and to

pleasing an audience, that is rewarding. Bat Boy is a wonderfully

self-contained, self-referential artistic expression of the meaninglessness

of modern culture, and its solipsism might be considered its fatal flaw.

But what matters fatality in a work concerned with regeneration, and

which also maintains a fortifying sense of materialism? When the play seeks

finally to explain itself, all exegeses revolve around this earth, the

here and now. Vampires are about as real as the Holy Ghost, the play proudly

proclaims.

Bat Boy’s book by Keythe Farley and Brian Flemming and its music

by Laurence O’Keefe are strong and vibrant and sweetly complementary. Much

of the book functions as operatic recitative, so the rhythm and musicality

seems never to completely fade away.

The leading voices, those of Chad Hudson (Bat Boy), Diana Preisler,

Daniel Siford, and Catherine Fries Vaughn, are exquisite. The chorus of

satyrs, which includes Mark Chambers, Billy Sharpe, Christina Parke, Brian

Natale, Carl Holder, Katrina Griffin, Leannis Maxwell, and Stephen Vendette,

is gangbusters.

Chad Hudson gives Bat Boy’s sweetness an edge, a stylish quirkiness.

He sells it. Buy it.

There is no truer portrayal however than Daniel Siford’s Dr. Parker,

whose searing soliloquies invite us to glimpse his wounded libido. His

angst is matched both by his frenetic wife, marvelously played by Catherine

Fries Vaughn, and his tempestuous daughter, alluringly embodied by Diana

Preisler. The wonder is that we feel for them all, never losing

sight of the object of their disaffection, Bat Boy, and his pitiful plight.

The Hipp heightens its atmospheric effects to unprecedented levels.

Mihai Ciupe’s chill and ornate stalagmite environment encloses an open

space for dance and movement while embracing the audience at the same time

– characters constantly popping up among us with the bright shock of a

jack-in-the-box.

Marilyn A. Wall’s costumes and puppets are stage magicians of themselves.

Tané DeKrey’s musical direction encompasses a stellar band capable

of a virtual compendium of musical theater, most of it to a double-beat

that quickens the pulse and lets the lyricism loose on the floor, where

the choreography of Ric Rose holds sway.

The satyrs are hustling all the way, working up a sweat, running laps

around the Hipp, running the stairs, popping in and out of the aisles

like pelvic thrusts.

The cartoonish grotesques of America are painted not so much with broad

strokes as with a bold filigree, like David Levine caricatures.

Lastly, Mark Chambers’ stint as Reverend Hightower, which kicks off

the second act, is blessedly brief, otherwise I would have fucking died

laughing.